We use educational design research, while combining innovative conceptual frameworks with embodied transformative experience

In developing our learning tools and trajectories we follow the systematic processes of educational design research, while bringing in cutting-edge conceptual frameworks as well abundant embodied experience with transformative learning.

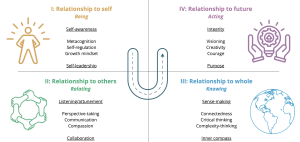

We’re currently in the process of developing (and publishing on) a new framework for envisioning the education of the future: the Essential Human Capabilities Framework.

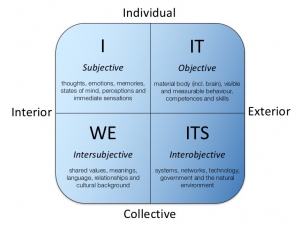

This framework is ultimely grounded in ken Wilber’s Four Quadrant Model of reality (see below). Other frameworks we draw on include the Big Questions that worldviews give answers to (concerning ontology, epistemology, axiology, anthropology, and societal vision), the Four Worldviews (traditional, modern, postmodern, integrative), and the five fundamental perspectives (subjective, intersubjective, objective, contextual, and planetary).

Using illuminating and clarifying frameworks combined with embodied practices (like inquiry, perspective-taking, and stream-of-consciousness journaling) can effectively create highly conducive conditions for transformative learning.

The Four-Quadrant model of reality

From as early on as Aristotle, there has been a philosophical attempt to classify objects and forms of knowledge in terms of basic categories. Think of the Beautiful, the Good, and the True. Or Art, Morals, and Science. Self, Culture, and Nature. Subjective, Intersubjective, and Objective. I, We, and It. First Person, Second Person, and Third Person.

Ken Wilber’s Four Quadrant Model builds forth on this effort and represents an elegant way to organize these general categories, by distinguishing between the interiors and exteriors of individuals and collectives (see the figure below). The realities disclosed in each of these quadrants are inextricably intertwined and co-evolving.

Since all events can be looked at in terms of all Four Quadrants, leaving out any of them will result in a partial perspective that lacks essential insight. We therefore use this model as a way to ensure a comprehensive approach. For example, when exploring worldviews we include a focus on self and awareness, on others and culture, on systems and nature, as well as on bodies and behaviors.